A Joint Meeting of the Australian and New Zealand Symposia of Gastronomy and Food History.

2014 - Wellington

29th November to the 1st December

______________

‘Ferment’

Convenors: Lois Daish & Duncan Galletly

PROGRAMME

Pre-Symposium Dinner - Ortega

SATURDAY

Hearty Breakfast

Welcome

Alison Vincent: A history of the Symposium in Australia.

Nancy Pollock: Finding Fermented Food in New Zealand.

Andre Taber: Bread without fermentation-the surprisingly long

history of chemical leavening.

- stretch legs (10mins) -

Penny Porritt: Tempeh, Miso….and Tofu.

Peter Howland: Connoisseurship by Proxy: A ferment of

democratized wine consumption, middle-class distinction and

reflexive tastes.

Alexy Simmons: Bottle, cask and pannikin.

Lunch

Duncan Galletly: Real cider… whatever that is.

Alison McKee: As Sour as Verjuice.

Jacqueline Dutton: From ferment to foment? European winemakers

in Burma.

Jeanette Fry: Rum - Corps, Currency and Rebellion.

Jeff Kennedy: "The short walk from Dixon Street to Jessie Street

that took 40 years".

Afternoon Tea

Nici Wickes: Good or just plain rotten? The importance of allowing

food trends to ferment.

Alana Clark: Reinventing Marmalade in the Colonies: When is an

orange not an orange, and grapefruit not a grapefruit.

Jenny Yee Collinson: Romancing the evolution of Vietnamese street

food in NZ.

End of Day 1.

Symposium Dinner - The Beijing (Newtown)

SUNDAY

Another Hearty Breakfast

Welcome

Kelda Haines: Fermentation- Flavour, Fear and Fashion.

Nicola Fraher: Cooking for Families… Fermentation at the Dinner

Table.

Margaret Brooker: Ferment in Food education.

- stretch legs (10mins) -

Janet Mitchell: Old Recipes, new ideas: The evolution of the

traditional NZ pikelet.

La Vergne Lehmann: A ferment of food waste – what contemporary

archaeology can tell us about the food we waste.

Lunch

Recipes and Kitchen Memorabilia. Discussion with Duncan

Galletly - New Zealand's earliest community cookery books.

Kate Hunter: Holding on to home. Cooking and Eating in Wartime.

1914-1918.

Helen Leach: Fermenting Division in the Kitchen.

Anne Else: Pinnies and pots: how women's food writing is perceived.

Christine Dann: The organic food evolution in NZ.

Lois Daish: The Great New Zealand Dish - 1969.

Mary Browne: From Beeton to Bloggers – the changing images of

food.

Afternoon Tea

Dave Veart: Dinner with Frank (Sargeson).

Jan Bennett: "My Nana's Cheesies".

Paul Schrader: "Service".

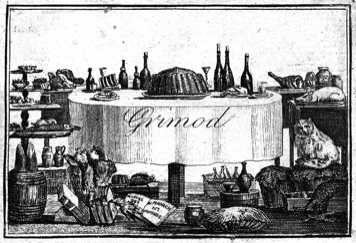

Duncan Galletly: The Aristologist.

End day 2.

ABSTRACTS

Alison Vincent: A History of the Symposium in Australia.

The first Symposium of Australian Gastronomy (SAG) was held in Adelaide in March 1984. Since then a Symposium has been held somewhere is Australia roughly every eighteen months or so, organised by an ad hoc committee of volunteers and based loosely around a few unwritten and uncodified conventions.

Thirty years on seems an appropriate time to look back at the origins of the SAG and its subsequent history. Described as 'a curiously Australian blend of creative art, science, scholarship, literature, wit and play', the SAG has established a reputation for the diversity of its participants, and in particular a mixing of amateurs and professionals, the variety of topics discussed, the interaction of theory and practice and the excellence and originality of the food provided. Intended to be a symposium in the original sense – a meeting to discuss and exchange ideas over food and wine - the essence of the SAG is a small group of people meeting as if for an extended dinner party, where the organising committee are the hosts and the attendees the guests.

Those who began the SAG did so with 'the ambition to develop gastronomy as a distinct discipline', however this would appear to have been a difficult concept to sell. Since 1984 the academic interest in food has escalated so that 'food studies' have become a focus for established disciplines within the humanities and social sciences. Today in addition to university courses, academic journals and regular conferences devoted to food there is more talk about food on television and more books relating to all manner of aspects of food production and consumption than ever before. And of course food is everywhere on the Internet. What then does the future hold for the SAG?

Nancy J. Pollock: Finding Fermented Food in New Zealand.

Early settlers brought with them to New Zealand a taste for fermented foods, whether Oceanic breadfruit or taro, or British bread and beer. Amidst their dilemma of finding any edible plants in the new land was their search for familiar fermented foods (Fischler's 2001 neophobia versus neophilia). Coming from Oceania where fermented breadfruit and taro were part of their diet, Maori ancestors eventually developed fermented corn, kaanga pirau (stinking corn). Later British arrivals sought ways of food processing to make bread and beer. What did they use as starters?

Both these communities were challenged to replicate a fermenting process in the new land. The acidity of fermented foods added a highly desirable new taste to their diet.

Andre Taber: Bread without fermentation-the surprisingly long

history of chemical leavening.

Food scientists call yeast "biological leavening" and steam "physical leavening". Baking powder produces "chemical leavening". But most cooks who use baking powder are naive about the fact that they are using chemicals, and creating reactions akin to the work of a chemistry lab.

This paper explores the history of chemical leavening from early documentary evidence to the development of commercial baking powder during the industrial revolution. The earliest record of chemical leavening is from a 14th-century Chinese text, a recipe for a forerunner to today's noodles and steamed buns, which includes the use of a chemical leavening sodium carbonate, which was manufactured either from mineral deposits or by collecting the ashes from burning sodium-rich plants. Evidence also suggests very early use of chemical leavening in the Netherlands, Germany, Scandinavia and Russia. In the 19th century the rapidly expanding chemical industry in Western Europe and North America turned its attention to the kitchen. After some development, the results were baking soda and baking powder, which remain pantry staples today, their formulations unchanged for a century and a half.

Peter Howland: Connoisseurship by Proxy: A ferment of democratized wine consumption, middle-class distinction and reflexive tastes.

'Connoisseurship has power for identifying the person as well as the wine. Not knowing may deliver one into the hands of manipulators' (Mary Douglas 1987: 9).

In the 17th century wine was transformed from a simple, bulk commodity to one distinguished by vineyard, vintage and grape varietals; by the ideally progressive ephemerality of cellaring; and which was increasingly consumed in singular units (i.e. by the bottle and/or glass) in public theatres of consumption such restaurants. This laid the foundations for the rise of wine connoisseurship and for the emerging middle-classes to forge conspicuous links with the elite social distinction associated with fine wine consumption.

In the 1970s New World wine industries moved to significantly democratize the cultural capitals of appreciative wine consumption. This was most evident in the adoption of varietal labelling and labelling that also included vineyard, vintage, taste characteristics and food-matching information; in the 'objective' certification of quality via wine show awards and/or wine critic reviews and ratings; and in tiered wine production, which provides multiple quality, price and market entry points. Democratization effectively enables connoisseurship by proxy and for middle-class individuals with variable wine tastes, experiences and aspirations to readily transform their economic capital into the cultural capital of appreciative wine consumption and into associated performances of high social distinction. Furthermore, the democratisation is significant in the various public theatres of consumption – such as vineyards, cafes and restaurants – where sufficient economic capital (which remains an obvious barrier to many), the minimal cultural capital of appropriate dress and behaviour, and an awareness that fine wine consumption is a mark of elite distinction are the primary requirements for performative participation.

Democratization does not, however, supplant wine connoisseurship as a form of elite distinction and high status is routinely assigned to winemakers, wine critics, Masters of Wine and others in possession of this cultural capital. Moreover, connoisseurship, high economic capital and/or VIP status in other fields routinely ensures entry into exclusive wine events such as invitation-only tastings, wine festivals, and to acquiring limited wine vintages. Thus democratization ensures wine industries maintain open markets, while simultaneously retaining the mechanisms and hierarchies of elite distinction based on elite wines and wine connoisseurship.

Democratisation strategies are significant in Martinborough, a boutique wine village and arguably an 'objectified' site of high quality wine production and for conspicuous performance of middle-class distinction. The majority of Martinborough's tourists can be classified as 'generalist' wine consumers. Nevertheless, by consuming democratised fine wines and performatively engaging in distinction by proxy on Martinborough's vineyards, cafes and restaurants, tourists are structurally enabled to reproduce middle-class distinctions alongside personalised or reflexive wine tastes and aspirations.

Alexy Simmons: Bottle, cask and pannikin.

Alcoholic beverages and soldiering go together like grease for frying. Liquor sustained the British and Colonial troops fighting to take and hold the central north Island of New Zealand from 1863 through the 1870s. Rum was issued as a daily military ration because it fortified the men prior to battle. Beer, wine, and brandy were acquired and used as personal 'medical comforts'.

War time journals, images, manuscripts, and archaeological remains document the role of alcohol in soldiers' daily lives and suggest fermented fare was as important to a soldier as their daily bread. The documents describe the military response to drunkenness and comment on wine and ginger beer brewing. Officers and the men both imbibed, but were constrained by different rules that affected the purchase, use, and storage of alcohol.

The presence of military men in the Waikato with fat pay packets stimulated grog sales. Canteen men and storekeepers eagerly served the troops from the early phases of active military engagements throughout the long period of occupation. The market demand for beer gave birth to the Waikato brewing industry. In 1865 Charles Innes established his first brewery in the frontier military camp of Ngaruawahia. Innes later became a household name associated with beer and aerated water.

Duncan Galletly: Real cider… whatever that is.

Cider has, over the past decade in New Zealand, gained enormously in popularity. The seemingly recent interest in the beverage seems to fit with the spin of advertisements claiming that cider has little New Zealand history until the first (and for many years only) real commercial cider was manufactured as "Rochdale Sparkling Cider" near Nelson in the 1940's. Certainly my own memories of the 1960s and 1970s seem to agree that Rochdale was, for many years, the only brand available. Yet this cider monoculture seems very odd given the popularity of cider "back home" in the 19th century, and the tendency of early colonists to try to transplant familiar tastes and comforts into their new environment. I wondered why the cider industry seemed so recent and lacking in diversity until recent times? This paper attempts to briefly explain cider manufacture and to look back beyond Rochdale at the considerable history that had existed before.

Jacqueline Dutton: From ferment to foment? European winemakers

in Burma.

Wine has been political ever since it was first fermented: in Classical times an amphora of wine was worth more than a slave, and wars have been fought over, across, under and through vineyards. In cultures that have a long tradition of winemaking and drinking, such politicisation of the product may be understandable. However, when a country like Burma opens its doors to tourists after 50 years of military junta rule, one does not expect to encounter European winemakers making quality grape wines in the highlands around Inle Lake. As a symbol of western bourgeois influence, wine is political by its very existence in Burma. The methods and means by which these winemakers operate in such difficult political and geographical climates suggest that the ferment they produce should inevitably lead to foment.

However, as Burma is changing, so are the tastes of its population. The influx of tourists over the last three years – tourist figures have skyrocketed from 300,000 in 2012 to 2 million in 2013 – have had an undeniable influence on the development of the grape wine industry. Gastronomically speaking, Burma does not (yet) have the status of Thailand, Vietnam or Laos, as most of the better restaurants in the tourist diamond - Yangon, Mandalay, Bagan and Inle Lake - serve European style or Thai/Indian fusion cuisine and imported wine. There is a growing market for more "authentic" food experiences, which also include "authentic" wine rather than the strong sweet beer, made by Myanmar (with US investment) or Dagon (Myanmar Economic Corporation). The country's military regime has been welcoming not just tourists but also foreign business, initially mainly from China and Thailand, and now from farther afield. Business means entertaining and as wine has become more popular in Asia, it has also become part of the business vernacular in Burma. The two major markets for wine in Burma are therefore foreign-based but a Burmese market is also evolving. Just as mobile telephones, cars, and western-style clothes are signifiers of success in Burma today, drinking wine is also an aspirational activity. In the midst of Burma's rapid social, economic and political transformation, this new homegrown ferment may not necessarily equate to foment…

Using ethnographic observational strategies and interviews with the only two grape winemakers in Burma – Frenchman Franois Raynal at Red Mountain and German Hans Leiendecker at Aythaya – this paper will analyse how these wineries have positioned themselves geographically, economically, politically and ethically in this unique context, where ferment and foment are constantly being re-negotiated.

Jeanette Fry: Rum - Corps, Currency and Rebellion.

A simple three-letter word, a catch-all for every type of spirit, has come to symbolise the first twenty five years of white Australia. Rum was far more than a fortifying drink in early New South Wales.

It quickly became the central driving element of the economy, the main form of currency and barter and the means by which power was obtained and exercised.

Rum was the tool by which the officers of the New South Wales Corps controlled the colony, enriched themselves and eventually led to Australia's only armed take-over of government. The rum economy led to the clash between the three most influential men in the colony in the first decade of the 19th Century, Governor William Bligh, Major George Johnston and John Macarthur. The rum trade corrupted the offices of state, distorted the struggling economy and also led to later depictions of early Australia as a hard drinking, lawless frontier society at the end of the world. Much of the story has been enhanced and mythologised over time, but the essential facts remain of a nation being forged under the influence of rum.

Nicola Fraher: Cooking for Families… Fermentation at the Dinner

Table.

I am a NZ Registered Dietitian, member of the NZ Food Writers' Guild and have just completed a Diploma of Professional Cookery at CPIT. I currently work as a Public Health Dietitian, promoting nutrition and the importance of enjoying cooking and eating to NZ families through my work with schools communities.

I believe there is a great opportunity currently for those of us who know about how to make food delicious, attractive, nutritious, affordable and fun (as well as quick and easy, at times) to work together to make this happen! There are so many players in this game!! We have the health industry, the food industry, the media and the NZ consumers, who all play a crucial role in this game - but the outcome must be sustainable in many ways, including maintaining the skill base required to cook nutritious meals and the support system and food environment that drives wellness.

I would like to present on my Public Health work around food and nutrition in schools and the huge changes we can make when we build solid relationships, provide information and knowledge and change environments. The Ministry of Health requires that our public health work results in improvements in whanau wellbeing so there was potential in the huge benefits that could be gained from cooking healthy meals and eating them together as a family – an opportunity to address the huge issue of loss of cooking skills! I have been lucky enough to be part of developing an NCEA resource that supports Home Economics teachers to teach a Level 1 Achievement Standard that involves students developing a healthy meal for their own family and then cooking it at home and sharing with them. They work on this project over a term and gain NCEA credits. The project ends with us filming a selected group of students cooking their meal with me for a local television station – I would show one of these 6min clips at the end (or can cut it down if needed).

The development of this resource has taken place over the last three years with input from local teachers, Health Promoting Schools advisors, Public Health Specialists and direction from NZQA. The project has been evaluated by the Community & Public Health Information team and I am able to report on the positive outcomes from this report, as well as some suggestions for others who may be interested in under-taking a similar piece of work.

Janet Mitchell: Old Recipes, new ideas: The evolution of the

traditional NZ pikelet.

Pikelets are a traditional New Zealand food, made with recipes bought to New Zealand by early settlers from the United Kingdom, and have appeared in New Zealand cookbooks since the 19th century. But evolution of the basic pikelet recipe has produced a derivative that New Zealanders call blini, usually found today as an internet recipe on cafe menus and as an item on catering menus to serve with drinks.

The traditional New Zealand pikelet was a quick flour based product often served at New Zealander's traditional morning, afternoon tea or supper. They were normally served buttered and sometimes with jam and cream. The blini is a traditional Russian dish made with buckwheat flour, yeast raised and traditionally served as an appetizer with toppings such as sour cream, smoked salmon or caviar. The NZ version of the same name is a hybrid. The recipe and cooking method used for the base is similar to pikelets but the toppings often suggested, sour cream or crme fraiche and smoked salmon reflect their Russian origin.

Changes in New Zealand eating patterns, new ingredients and processing methods have created a whole new position for the humble pikelet in New Zealand cuisine.

La Vergne Lehmann: A ferment of food waste – what contemporary

archaeology can tell us about the food we waste.

Changes to lifestyles, working habits, food storage technology, food health standards and labelling, food availability along with increased knowledge of different cultural food options have inevitably changed what and how people prepare food, consume food and consequently waste food. Over the last half a century, the emergence of super markets as the primary food purchasing option for many consumers has changed the nature of food consumption habits. No longer is unpackaged fresh food the primary source of nutrition and today supermarket options range from packaged fresh food through to completely pre-packaged meals and many alternatives in between. In short, the food supermarket has changed the modern diet forever.

At the same time we are also producing more food waste than ever. Recent audits and surveys in Australia suggest that food makes up around 40 percent of the contents in the household garbage bin. This translates into more than $1000 of food waste per household each year. There are many reasons for this growing level of waste including poor storage habits, over-purchasing and cooking and a lack of understanding about food in general. It may also be the case that supermarkets themselves are contributing significantly to the food waste problem with their consumer purchase options. Understanding what consumers are purchasing and throwing out is therefore critical in understanding what food is being wasted.

Leading the way is using contemporary archaeology to gain a better understanding of modern consumer habits Dr Bill Rathje's Garbage Project initially began as a practical activity for archaeology students at the University of Arizona. The Garbage Project provided a platform for understanding of contemporary society's consumer habits through the prism of household waste. For nearly two decades the Garbage Project was able to study consumer behaviours directly from the material realities they left behind rather than from traditional self-conscious self-reports of surveys and interviews.

Using the same rationale, this study looks at three separate samples of general waste intended for landfill and recycling waste intended for a materials recycling facility (MRF) to develop a profile of the packaged and processed food consumption in three different regional Australian communities. This study was limited to packaged and processed food items disposed of by the range of small communities with limited access to a retail options in their locale. Once the nature of the packaged food was identified, some analysis on the type of products that were consumed, how they might have been consumed and how much was wasted was undertaken.

By understanding the nature of the packaging and food that is being thrown away, it has been possible to develop a narrative around what people understand about food, how they use it and may have the potential to direct better information to consumers about food storage, use by and best by dates and shopping habits.

Kate Hunter: Holding on to home. Cooking and Eating in Wartime.

1914-1918.

When you start looking, food appears everywhere in the history of WWI. Beyond rations, hard tack and jam – those reasonably well known aspects of wartime life – wine, vegetable gardens, meat paste and New Zealand butter all appear in soldiers' and nurses' writings. Drawing on my latest project about the objects and materials of WWI, I want to show the breadth of evidence about food, cooking and eating that appears in the archive of the Great War.

Helen Leach: Fermenting Division in the Kitchen.

The interactions of the staff at Downton Abbey remind us that the kitchen has long been the site of social ranking and division. We are familiar with many different types of hierarchy, such as those based on birth, military rank, and gender. This paper will examine another source of division in the kitchen, that inherent in the opposition of amateur and professional.

I will start by presenting two apparently unrelated statements relating to professionalism in cookery: the first is a 1993 advertisement for stainless steel appliances, and the second is a review article on the recently published The Great New Zealand Cookbook. Underlying both is a belief in the superior status of the professional cook.

Professional reassessment of amateurs' needs was involved in the elimination of 'home' from the names of Home Science and Home Economics organisations in the late 20th century. That change saw the down-grading of the productive 'home-maker' to a passive consumer. When the history of gastronomy is examined, the amateur-professional dichotomy has been marked by mostly unsuccessful attempts to win academic acceptance for the subject. Significantly, gastronomy is encumbered by its long-term association with fine dining, accepted as a marker of high social class for over 2000 years.

Christine Dann: The organic food evolution in NZ.

All food starts in the soil. Humans eat plants, and animals that eat plants. The quality of the soil that plants 'eat' is critical to the nutritional quality of the food that humans eat. High-quality soils are rich in humus, formed by the breakdown of organic matter. This is something that was well-understood by those who founded New Zealand's – and the world's – first organic gardening association, the Humic Compost Club, in Auckland in 1941.

Between 1941 and 2001 the world changed dramatically in many ways. Humic Compost Club members were focused on growing as much good food at home as possible, to improve the nation's health and wealth during World War Two. To suggest that sixty years on Christchurch would have an organic Japanese restaurant, and organic exports from New Zealand would be worth hundreds of millions of dollars, would have seemed beyond the bounds of possibility.

Yet this is what actually happened. In this paper I explore how we got to here from there, and where we might be going next.

Mary Browne: From Beeton to Bloggers – the changing images of

food.

This slide presentation is an overview of the photographs and illustrations found in a personal collection of cookbooks and gastronomy magazines, from Mrs Beeton to current bloggers.

Cookery illustrations have a distinct and separate history from the recipes they accompany. Except where the food writer produces his or her own photographs or drawings. I will argue that the control over illustrations in most cookbooks and magazines rests with publishers with marketing constraints, advertisers, stylists, and professional photographers. Compared to the recipes, the images therefore are much more subject to changes in technology and style coming from outside the kitchen.